How to Learn Better in the Digital Age

November 2020

Before I got into productivity and performance, I used to spend many hours online ingesting vast troves of digital content. My information diet ranged from inspirational TED talks to specialized podcasts, from blog posts found on Hacker News to ebooks shared on Twitter.

I’m deeply curious, and I gave in to new content as much as I could. What could be the harm?—I thought. I loved spending my time this way. It felt useful, it was fun, and it nurtured my self-image as a “smart guy” — all at the same time. Truly, a learning hack.

Turns out I wasn't hacking anything: The learning wasn’t real.

A few months ago, doubts began to creep into my mind about the effectiveness of my habits.

While I’d amped up my information consumption, I wasn’t retaining most of it. My memory was behaving like a leaky bucket. Sure, I was spending tens of hours listening to politics on the radio. But when I tried to use any of those points in a conversation, I found that I didn't actually know enough to make a coherent argument. I knew the surrounding context, but the moment I needed to get specific my argument would crumble. Same for many other topics: the more technical they were, the less retention I had.

Where did all that information go?

The problem lied in how I was seeing learning, and therefore how I was approaching it.

Learning is what turns information consumption into long-lasting knowledge. The two things are different: while information is ephemeral, true knowledge is foundational. If knowledge were a person, information would be its picture.

It’s easy to think of learning in accretive, cumulative terms: if I stack up enough information, it will eventually turn into knowledge. We tend to judge the world in material terms, and if data were tangible, an indefinitely growing memory might be reasonable to assume. The more information I consume, the more information I store, the information data I can later retrieve. The more business newsletters I’ll read, the more I’ll know business.

However, this line of thinking wasn’t really applicable to my case: I was undoubtedly consuming many business newsletters each week, but that wasn’t translating into long-term business knowledge.

I spent the last eight months trying to find an answer to this riddle. It took me deep into the topic of meta-learning: How do humans learn? And how can we learn better in the digital information age?

Learning must be effortful

Unfortunately for us, human memory does not resemble storage, and “passive accumulation” isn’t how learning happens.

The truth is that we retain information only when we put serious effort into the process of learning. The intrinsic effortfulness of learning is not just a byproduct of the core activity, like shortness of breath during running. On the contrary: it’s what actually enables it. The relationship is causal.

I didn’t find a learning hack to avoid effort because there’s no such thing as easy learning: learning must be effortful in order for it to happen.

What surprised me the most is that learning is far more grounded in the physical world than I was comfortable admitting.

The most literal meaning of effort is physical effort (think of weight lifting at the gym). The same holds true with information retention: it works best when the process of assimilating it is physically effortful. Our memory shines when our learning is physical, visceral, and obvious, like the aching in your hands after a morning spent hand-writing.

Since they’re passive, easy, and exclusively digital, after this realization all my podcasts, e-books, audiobooks, newsletters, blog posts, videos, live webinars were suddenly deprived of their “learning status”. Instead, they assumed their proper place in my schedule as pure entertainment activities.

The fact of the matter is that digital products make it uniquely easy to trick yourself into thinking that you’re learning when you are actually being entertained.

What I still didn’t know was why our mind works like this. Is this just the current state of digital learning and teaching, or there’s actually a margin for easy learning to be found somewhere?

The neurology of learning

I’m no expert in medicine, let alone neurology, but I did want to roughly understand what happens when we — as humans — create knowledge. Luckily I didn’t need profound medical expertise to get the gist of the matter.

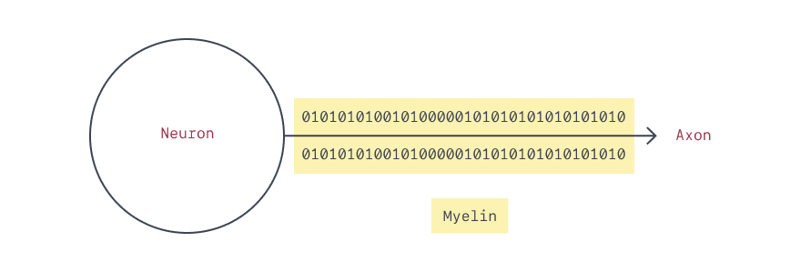

Our brain is made of a web of interconnected neurons. The links between these neurons are called axons: long, slender projections of nerve fibers that transmit electrical impulses.

Around these axons, there’s an insulating membrane called myelin. It covers many neuronal axons and facilitates the propagation of electrical signals along neuronal circuits. The more myelin around an axon, the stronger and more connected the signal transmission will be.

Myelin is to neural transmissions as oxygen is to fire. It allows rapid information transfer over long distances, and it greatly increases the speed of propagation of electric signals in our brain.

See it as water flowing through a pipe with dynamic, changing capacity. Pipes with greater capacity can move more water, more quickly than a small pipe or a slow drip. The more myelin supporting a neural connection, the easier it is to use that connection — and thus to use the skill or remember the topic associated with that connection

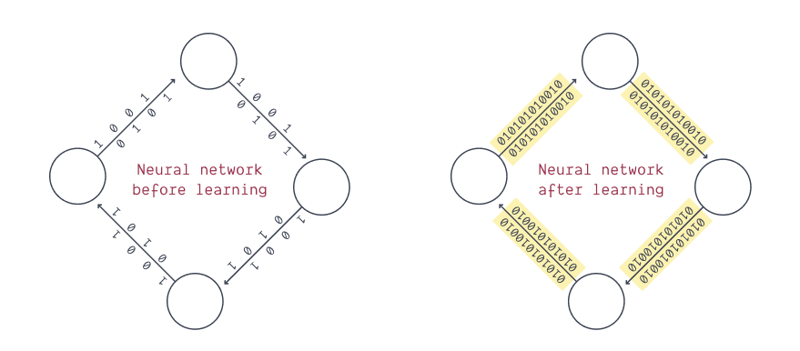

A key aspect of myelin is that it’s highly dynamic. It’s an integral component of our brain plasticity. So the question becomes: how is myelin generated, and why?

When we come across a new topic, new regions of the brain start activating. The more we use those new regions, the more myelin is synthesized, the easier that topic (or activity) gets.

We all know the old saying practice makes perfect. The more we use a certain region of our brain, the more our brain "prioritizes" and "hones" it. That is what leads to myelin: activity induces myelination, which leads to increased strength of connectivity and efficiency along those very neurons. It’s a self-reinforcing process.

In other words, it compounds.

See now why it’s so hard to learn? To learn anything we must make active use of unexplored regions of our brain before they're ready. It's, quite literally, getting out of the comfort zone. The more we use them, the more they get better. Learning is structurally hard.

The truly mesmerizing thing about myelination is that it is correlated with active use of motor neurons. It looks like human cognition is fundamentally grounded in sensory-motor processes: we retain information better when we associate some physical activity to it. The general intuition is that movement provides additional cues we can use to retrieve knowledge.

We can see this effect happening when we take notes. A larger corpus of research is suggesting that taking notes physically — that is, by hand-writing them — is far more effective than using a laptop. Keyboarding does not provide tactile feedback to the brain that the contact between pencil and paper does: this contact, this raw feedback, is the key to creating the neurocircuitry in the hand-brain complex, that evidence shows supports memory and retention.

All of this means we need to radically reassess digital learning. We haven’t evolved to store information by passively watching Masterclass videos: that’s just not how our minds work.

However, the other side of this coin is that we’re living in times of unprecedented information surplus. This is an opportunity that we should learn to seize.

Creative learning in a digital world

The best way to describe my information diet before discovering that effort is instrumental to learning would be edutainment.

Edutainment mixes education topics with entertainment methodologies. Even if edutainment optimizes for passive attention instead of effortful engagement (the opposite of learning), it’s not just “mere fun.” Deleting Twitter and unsubscribing from newsletters, as suggested by Deep Work advocates like Cal Newport, can actually end up preventing learning.

I see edutainment as preparation for learning: it’s a powerful explorative tool that can provide ideas and motivation to learn. And yet, it’s also not learning itself, in the same way as buying running shoes is not running.

Within this framework, “mindless” browsing online can be transformed into scouting for learning opportunities. It’s yet another searching problem where it’s key to balance the exploration of new opportunities with the commitment to the existing ones — a topic I wrote about at length in another essay. It’s about balancing the time spent “scouting” for interesting topics online with the offline effort needed for long-term retention and integration.

Pragmatically, I solved this trade-off with a powerful tool: a learning inbox.

A learning inbox is a to-do list for stuff I’d like to actually learn. I picked up the idea from Andy Matuschak — legendary ed-tech expert —, who used a similar concept as a tool for capturing possibly-useful references. The learning inbox is a system that forces me to be mindful about what content is learning, and what is at the end of the day just entertainment.

Everything interesting I find on my way is sent to my learning inbox and from there gets triaged, be it a paper, an online essay, a blog post, a YouTube video, or a podcast. When an item ends up in there, there are three things that can happen: I either decide to actively engage with it, to file for future interest, or just trash it. Active engagement is exactly what it sounds like: I need to take effortful action to consume the content in the list, otherwise I automatically bucket it as entertainment.

In other words, I need to do something with it. To create something. Write a blog post about it, use it in a new project, test it on the field, teach it at a meetup. That’s why I speak at many conferences: it’s a learning tool.

In GTD fashion, permanence in this list is temporary. It's a release valve, not a procrastination tool.

For example, I recently came across a tweet during the last Election day mentioning a video about computational democracy. I’m extremely interested in the intersection between politics and data, so I sent the link to my learning inbox (a task on Things 3) – and then promptly forgot about it.

A few days later, during one of my ritual learning sprints, I took out my notepad and watched the whole video while taking handwritten notes. I then reviewed and transcribed what I had jotted down to an evergreen digital note in my personal knowledge base. The whole process took twice as long as watching the video, and it’s not even a done deal: I would still need some kind of experimentation, tinkering, iteration, application in different contexts, and generally something more hands-on than just note-taking to significantly solidify my knowledge on the topic. That’s what learning takes.

The process takes a lot of time and effort, which means it’s not something I can afford to do with every piece of content I find online. Most of the time I trash the links I find, upon further review. Sometimes they end up in my learning wish list.

The core idea is trying my best to not kid myself: when my engagement with a piece of content is active and effortful then it’s learning, when it’s passive it’s entertainment. When I create I learn. When I consume I just relax.

Bottom line: we need to engage with what we encounter if we wish to absorb it long term. In a smartphone-driven society, real engagement, beyond the share or like or retweet, got fundamentally difficult – or, put another way, not engaging got fundamentally easier. Passive browsing is addictive: the whole information supply chain is optimized for time spent in-app, not for retention and proactivity.

Luckily, the other side of the coin is that finding new topics and new reasons to learn got dramatically easier, with such an abundance of content and stimuli.

We just need to be proactive with how we engage with all of the streams of content available to us. To go out and build, write, talk, teach, explain, create — effortful actions, that lead to meaningful growth.

That's for sure what I’m going to do.

• • •