Why Ed-tech Startups Don't Scale

November 2022

This is an updated version of the original essay. Last update: 2025.

--

I have yet to find a successful ed-tech model that works at scale. Issues abound, but they often come down to how ed-tech products grow and how they monetize their audiences.

Let’s start with growth.

The education market is geographically siloed, making it hard to follow the typical growth playbook of venture-backed businesses. When the structure of demand is similar across geographies, a product can grow unchecked. For education, though, each region has wildly different needs — from the subjects taught to cultural expectations, from standardized testing requirements to different legal frameworks.

In the US, most college students take internships every year. In Europe, the majority do it just once. In most anglosaxon countries there are several ways to finance a college degree, from grants, to student loans, to tax-advantaged savings accounts. In Italy, the price is low enough that many students pay for their studies while working part-time as waiters or store clerks. In Germany, it’s completely free.

As an edtech early-stage startup that has just found product-market fit in one region, you are unlikely to scale by simply replicating your model. The moment you change the market part of the equation, you’re forced to change the product too.

You’ll quickly face a conundrum: dilute your product-market fit by geographically expanding the product, or forgo growth and hunker down in your initial market. The former will result in a lot of churn as you acquire users who aren’t the right fit for your product, while the latter means capping your growth potential and losing the steam needed to reach venture scale.

You can build a successful internship product in the States — like Handshake, a career recruiting network for college students — but you’ll end up facing an uphill battle in most other countries because the need for is simply not there. You can build a successful tutoring business in South Korea, but you’ll have a hard time bringing it to other countries where it’s not a dominant part of their culture.

This was the issue when I built Uniwhere, the first mobile app to manage college life end-to-end in Italy. Ultimately, it made us sell our company. We found a near perfect product-market fit in Italy that did not easily transfer to adjacent markets in Europe and North America. And we tried — hard.

To be clear, product localization is challenging in any product category. There’s always hardship to overcome when scaling, especially across cultures and markets. To make the investment make sense, growth friction has to be offset by larger expected returns: more customers to reach, more money to make.

Some businesses have it easy. Products like Netflix, Airbnb, or Doordash capitalize on consumer habits that cross borders and cultures, which is why they can scale seemingly effortlessly. The product experience you get from Disney Plus in Ecuador is the same as the experience you’ll get in Mongolia because the nature of the entertainment demand is practically identical. For other businesses the growth friction is low because their product is malleable and adaptable, catering to very different needs while preserving its original shape. These are exceedingly rare, and objectively magical products. It’s the case of ChatGPT and Google.

Education is not like that. Inter-market differences are profound, almost unshakable, and extremely granular.

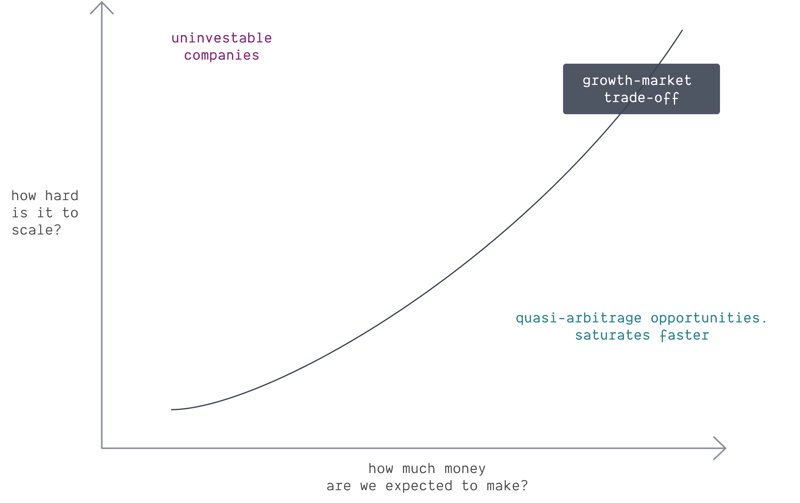

That’s not necessarily a show stopper. Sometimes, even when there’s friction, it’s worth it. Some industries that are hard to scale across borders will still see generational companies form because the expected returns are so incredibly large. In the transportation market, Uber’s global presence led to a $176b market cap, despite every city requiring its own licenses, labor rules, and insurance regime. In the HR SaaS market, Rippling's most recent round valued it at $13.5b, while threading dozens of country-specific labor, tax, and data-privacy codes. In both instances, while scaling geographically has been tremendously hard and painfully ad-hoc, it was worth it.

In education, though, expected returns are just too small to offset fragmentation on the demand side. Money too, and not just growth, is hard when it comes to ed-tech.

A lot of why this is the case boils down to misaligned incentives: while parents pay, students consume. Education products are rarely optimized for their real users.

It can all easily become a giant, messy, jigsaw puzzle: institutions pay for the product, educators administer the product, students consume the product, and parents passively evaluate the performance of the product. It’s an intrinsically hard design problem. Too many parties to satisfy. Ed-tech companies end up optimizing for the buyer demands, rather than for meaningful user experiences. This misalignment pushes the market toward offering low prices, easy compliance, or even the ability to brag with other parents — rather than actual, durable learning.

What ends up happening is a race to the bottom on either price or quality, which means most K-12 ed-tech products either suck or don’t sell.

To solve this issue, you can instead only focus on users who can pay: adults. At that point though you’ll run into yet another problem: the time horizon is too long. While you need to learn now, benefits come much later. Most people hate to invest time and money in things that may or may not benefit them for months, or years, and they’ll reliably choose smaller immediate rewards over larger, delayed gains (a phenomenon known as “hyperbolic discounting”). It’s the famous marshmallow test. The majority of consumers will rather have one now than *maybe *two later.

Startups have found novel ways around this cognitive bias — but all of them have shortcomings.

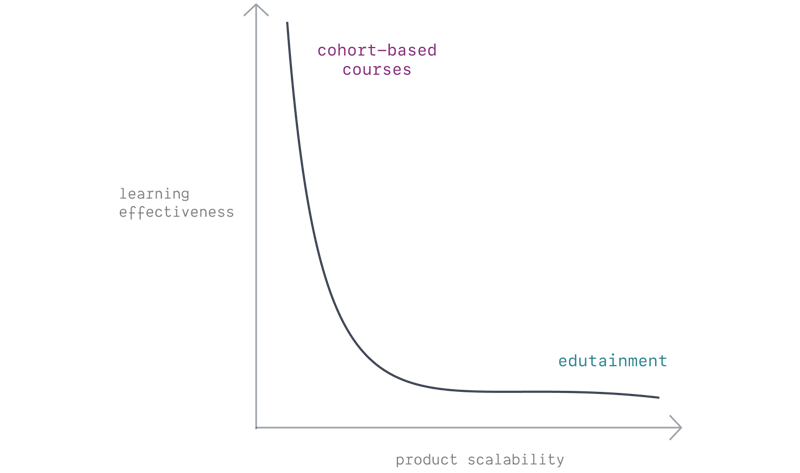

The first way is to bundle users together in small groups, or so-called “cohort-based courses” (CBCs). These lend themselves to rather successful (and often enjoyable) learning experiences — but they’re basically impossible to scale without severely diluting the product quality. The best experience is to have a few peers to keep you accountable and motivated, but not enough to forgo a personalized dedicated approach from a world-class teacher.

The second way is to gamify learning. A classic example is Duolingo, now a tremendously successful company with an over $24b market cap. My qualm is that Duolinguo is not actually an education business: it’s a gaming app. Learning (very much like exercising) must be hard to be effective. For a host of psychological and biological reasons, the more effort you put in, the more effective it will be. This reality is at odds with building a product optimized for engagement, which increases as you remove friction and effort from the act of learning.

Duolinguo is not in the business of teaching languages. It’s in the business of letting smart people play with their phones without making them feel like they’re wasting their time.

Other companies, the most famous being Bloom Tech (once upon a time known as Lambda School), tried to solve the time-horizon issue by postponing payment. They popularized Income Sharing Agreements, a way for education providers to get paid later using a portion of the student’s future income. It was a powerful idea, at the time, but it suffered from the same scaling and monetization issue as any other cohort-based course: scale and quality are at odds. To squeeze more out of it Bloom Tech resorted to aggressive financial engineering, bundling the student loans and reselling them to sophisticated investors while mischaracterizing the loan nature, ending up burning the company’s brand.

Okay. Making people pay for education is hard at scale. What about advertising? A few startups have been building a platform where people learn economically valuable skills for free, and all recruiters pay to reach them. If you can’t sell content — the thinking goes — you can sell access to your customers, that you acquire cheaply before upskilling them. Recruiting and education are two sides of the same coin: it’s an ingenious plan.

Unfortunately, that too doesn’t work.

One reason is that customers who need the product most — small companies and local businesses who can’t fill roles — are those with the least amount of money to pay. There’s also an extreme variance between small and big companies’ recruiting needs, that reminds of (and is maybe partially attributable to) the regional fragmentation in the education market. Recruiting businesses have the same scaling issues as education startups: they’re geographically siloed and become less profitable and less marginally efficient as they grow.

Another potential angle of attack is to make companies pay for content in service of employee reskilling and retention. So far, I haven’t seen it work either. Large companies can leverage a higher base comp and better employer branding to attract and retain employees — which is much more effective than pure reskilling. Typically, when large companies invest in educational content for their workforce, they’d rather make their own materials and tools when they can afford to do so; if we consider only those who can’t invest in bespoke solutions, the market shrinks considerably.

My experience as an edtech founder leads me to believe the only effective way to easily monetize ed-tech products at scale today is to avoid the “education” part in the first place, and to sell entertainment instead. Aside from Duolinguo, Masterclass is another great example. Substacks, YouTube channels, Morning Brew, and even magazines like The Economist fall into this category. Edutainment is pleasant and immediately satisfying. It can work spectacularly well, as a business. But while it may effectively convey knowledge and information, its memory decay curve will be steep because of the lack of effort and hardship involved in its (passive) consumption. It doesn’t accrue to actual new skills or long-term retention.

It’s not education.

---

Despite these issues, some ed-tech companies have managed to become robust global businesses: Udemy, ClassDojo, Lynda (acquired by LinkedIn), Coursera. They leveraged product primitives that quickly saturated, and today are no longer exploitable. More interestingly, however, none of them are what I’d consider generational companies with wide cultural and economic impact.

Take Udemy, for example: it’s a peer-to-peer marketplace. From a product design perspective, it’s no different from eBay, or Uber. It’s the startup class of the early 2000s. And, most critically, a billion market cap that fell off a cliff in the last few years. Interestingly and specularly, after years staying in the same market cap class, when Duolinguo finally decided to lean into what truly works for them and started optimizing for long term usage rather than long term memory retention, it increased its valuation by an order of magnitude.

In education, you’ll either find companies with high PMF that never scale beyond their initial successes (eg. Uniwhere), or companies that can scale but can’t achieve high PMF because regional players will always build better products — and better products on a smaller scale will inevitably monetize better. You’ll also find a lot of distracting entertainment masquerading as education.

This is why the ed-tech landscape is highly balkanized and, for founders, has so far been largely unrewarding. It’s too capital-intensive to compete when the upside is so low and the likelihood of global success so minuscule.

At the same time, I don't want to say that building a venture-scale, generational company in the education space can’t be done. In fact, I think things may finally be beginning to change.

In contrast to a few years ago, when I first wrote about this topic, AI today is a legitimately new element to the ed-tech formula. It combines what’s already powerful about information technology (nearly perfect memory), with something that has been elusive until recently: scalable genuine personalization. This potentially nullifies the scalability-vs-effectiveness trade off: we can now finally see products that do provide true long-term learning while catering to the individual needs and cultures of its users.

While this is incredibly encouraging, it still doesn’t solve some of the monetization issues that are at the heart of the ed-tech problem — and may even introduce new ones. Companies must now suffer sizable marginal costs to build compelling products, which makes generating profit even harder. There’s also a novel market dynamic, with fierce competition from do-it-all behemoths like ChatGPT coupled with downward pressure coming from a plethora of small startups using their very technology.

All things considered, I’m positive someone will figure it out.

It's just so hard that no one has yet.

• • •